The conceptual framework of this manual

Living Democracy » Textbooks » The conceptual framework of this manual1. Basic principles of EDC/HRE

Active citizenship is best learned by doing, not through being told about it – individuals need to be given opportunities to explore issues of democratic citizenship and human rights for themselves, not to be told how they must think or behave. Education for active citizenship is not just about the absorption of factual knowledge, but about practical understanding, skills and aptitudes, values and characters. The medium is the message – students can learn as much about democratic citizenship by the example they are set by teachers and the ways in which school life is organised, as they can through formal methods of instruction.

These principles have a number of important implications for the learning processes in EDC/HRE, namely:

a) Active learning

Learning in EDC/HRE should emphasise active learning. Active learning is learning by doing. It is learning through experiencing situations and solving problems oneself, instead of being told the answers by someone else. Active learning is sometimes referred to as “experiential” learning.

Active learning is important in EDC/HRE because being a citizen is a practical activity. People learn about democracy and human rights through experiencing them, not just by being told about them. In formal education, this experience begins in the classroom, but it continues through the ethos and culture of the school or college. It is sometimes referred to as teaching through democracy or through human rights.

Active learning can also be a more stimulating and motivating form of learning than formal instruction and can bring about longer-lasting learning – both for adults and young people – because the learners are personally involved. It also helps learning because it focuses on concrete examples rather than abstract principles. In active learning, students are encouraged to draw out general principles from concrete cases, not vice versa: for example, considering different types of rights based on a specifi c “rights” issue in school – such as school rules or codes of behaviour – rather than through an abstract discussion of the concept of rights.

b) Task-based activities

Learning in EDC/HRE should be based around the tasks that teachers themselves need to carry out during the course of teaching EDC/HRE. This manual therefore follows the principles of task-based learning.

Task-based learning is important for a number of reasons:

- It is an excellent form of active learning – that is, learning by doing.

- It provides a structure for different learning settings.

- It maximises the time available for learning as students are working on tasks that they have to do anyway.

- It provides real-life problems to solve and authentic material to analyse.

- It makes learning more meaningful and therefore more stimulating.

- It gives learners a sense of ownership and achievement.

c) Team work

EDC/HRE should emphasise collaborative forms of learning such as working in pairs, in small groups or larger groups and/or in peer support groups. Working in teams is important because:

- It provides learners with models of collaborative group work that they can apply in the classroom.

- It encourages students to exchange their experiences and opinions and, by sharing their problems, it helps to increase the chances of solving them.

- It acts as a counterbalance to the experience of standing alone in a classroom.

d) Interactive methods

EDC/HRE should emphasise interactive methods, such as discussions and debates. Interactive methods are important because:

- They help teachers learn how to use interactive methods in their own teaching.

- It is a way of encouraging teachers to become active participants in their own training.

e) Critical thinking

Good EDC/HRE encourages students to ref ect upon issues of EDC/HRE for themselves, rather than be supplied with “ready-made” answers by teachers. This is important because:

It helps learners to think for themselves – an essential attribute of democratic citizenship.

It gives them a sense of ownership and empowerment: they feel able to take responsibility for the lives of all students.

f) Participation

EDC/HRE gives students opportunities to contribute to the training process. As far as possible, they should be encouraged to be active in their learning rather than the passive recipients of knowledge – for example, by choosing the tasks they wish to work on, evaluating their own strengths and weak-nesses and setting targets for how they might improve.

An element of participation is important because:

- It helps learners learn how to build participation into their life outside of school.

- It empowers them and gives them a sense of ownership.

In a nutshell, EDC/HRE is:

|

2. Three dimensions of competence

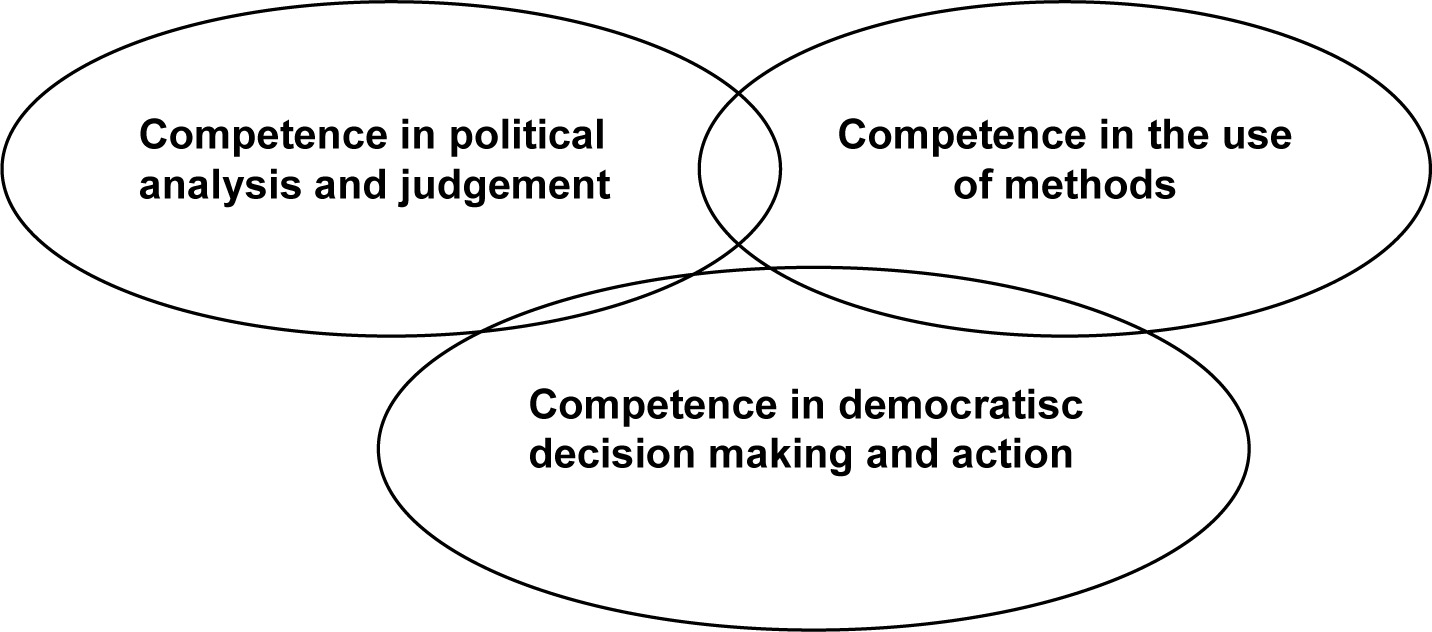

The aim of education for democratic citizenship and human rights education is to support the development of competences in three areas: political analysis and judgment, the use of methods, and political decision making and action, all of which are closely linked and therefore should not be treated separately.

In every learning setting – whether consciously or unconsciously – there will be elements of all three competences, but not all will be touched on at the same level of depth. This is not necessary. It is possible to sometimes concentrate more on methods, sometimes more on action and sometimes more on analysis. In each unit, we give a rough estimate of the extent to which the three competences will be developed, using a table similar to the example below. Three stars indicate a high level, two stars an average level, and one star a low level. Nevertheless, it will depend on teaching methods and the selection of learning situations whether some of the competences will become more important than foreseen.

| Competence in … | ||

| … political analysis and judgment | … the use of methods | … political decision making and action |

| ** | * | *** |

Below is a brief overview of the three competences in EDC and HRE. This concept of three competences is widely discussed in political science and as yet there is no def nitive answer to this discussion.2

| A. Competence in political analysis and judgment The ability to analyse and dis-cuss political events, problems and controversial issues, as well as questions concerning eco-nomic and social development, by considering aspects and val-ues of the subject matter. |

B. Competence in the use of methods The acquisition of the abilities and skills to find and absorb information, to use means and media of communication, and to participate in public debate and decision making. |

C. Competence in democratic decision making and action The ability to express opinions, values and interests appropri-ately in public. The ability to negotiate and compromise. |

A. Competence in political analysis and judgment

The aim is to develop the competence to analyse political events, problems and controversial issues and to enable students to explain the reasons for their personal judgments. School can contribute to this process by supporting students in using structured approaches based on key concepts to arrive at a higher level of critical thinking.

To enable the students to develop this level of judgment, which should be carefully thought out, the following competences are necessary:

- The ability to understand the importance of political decisions for one’s own life.

- The ability to understand and judge the outcomes of political decisions – both intentional and unintentional – affecting actors and non-actors.

- The ability to understand and present one’s personal point of view and that of others.

- The ability to understand and apply the three-dimensional model of politics: a) the institutional b) the content-bound and c) the process-oriented dimension.

- The ability to analyse and assess the different phases of political processes at micro-level (school life), meso-level (community) and at macro-level (national and international politics), applying both the principles of democratic governance and human rights.

- The ability to present facts, problems and decisions with the help of analytical categories, identifying the main aspects and relating them to the fundamental values of human rights and demo-cratic systems.

- The ability to identify the social, legal, economic, environmental and international conditions, as well as interests and developments in discussions about current controversial issues.

- The ability to understand and assess the manner in which political matters are presented by the media.

B. Competence in the use of methods

In order to be able to take part in the various political processes, it is not only necessary to have basic knowledge of political issues, constitutional and legal frameworks and decision-making processes, but also to have general competences that are acquired as part of other subjects (such as communication, co-operation, dealing with information, data and statistics). Special abilities and skills, such as being able to argue for or against an issue, which are particularly important for taking part in political events, must be trained and promoted in education for democratic citizenship and human rights education. This places an emphasis on task-based learning, as task setting is crucial for competence development. In EDC/HRE, suitable methods to simulate or support controversies in public are widespread (i.e. discussions and debates). In order to be able to do this, the following skills are necessary:

- The ability to work independently in f nding, selecting, using and presenting information given by the mass media and/or new media in a critical and focused manner (making use of statistics, maps, diagrams, charts, cartoons, etc.).

- The ability to use media critically and to develop one’s own media products.

- The ability to perform research, i.e. to acquire information from original sources through surveys and interviews.

C. Competence in democratic decision making and action

The aim is to acquire the facility to interact conf dently and adequately in political settings and in public. In order to be able to do this, the following abilities and attitudes are necessary:

- The ability to voice one’s political opinion in an adequate and self-confident way and to master different forms of dialogue, debate and discussion.

- The ability to take part in public life and to act politically (arguing, discussing, debating, chairing a discussion; or preparing a written presentation and visualisation techniques for posters, wall newspapers, minutes of a meeting, letters to the editor, petition-writing, etc.).

- To be able to recognise one’s own possibilities to exert political influence, and have the ability to form coalitions with others.

- The ability to assert one’s point, but also to compromise.

- The willingness and ability to recognise anti-democratic ideas and players and to respond to them appropriately.

- The willingness and ability to behave openly and in a spirit of understanding in an intercultural context.

3. Key concepts as the core of the nine units

Thinking and learning have a lot to do with linking the concrete with the abstract. The key concepts in this manual, as well as those in the EDC/HRE volumes for secondary I (Volume III: Living in democracy) and secondary II (Volume IV: Taking part in democracy), have therefore been developed using concrete examples and focus on interactive learning situations.

The artist who designed the cover page has drawn nine puzzle pieces, one for each unit. Together they form a complete puzzle. This indicates that the nine concepts are linked in many ways and form one meaningful whole. It is equally important to know that each unit can also be used as a stand-alone unit and so each piece of the puzzle has an intrinsic value. All nine units together have the potential to f ll one year of EDC/HRE teaching.

A picture is worth more than a thousand words, so the proverb goes. This puzzle can tell the reader a great deal about the key concepts in this manual, about the implications of making didactic choices, and about constructivist learning.

2. For further reading, see the Council of Europe publication How all teachers can support citizenship and human rights education: a framework for the development of competences (2009). The manual can be downloaded or ordered on the website www.coe.int/edc.