The fishing conflict

How can we solve the sustainability dilemma?

Introduction for teachers

1. What this unit is about

This unit focuses on the problem of how to manage common resources. If political decision makers, companies and citizens fail to solve problems of this type, they may lead to serious conflict and even to war.

To illustrate the issue, imagine the following everyday situation: in a cinema, full of visitors, a small person cannot see much because a giant 1.90 metres tall happens to be sitting in front of him. So the small person stands up. But now other visitors have a blocked view, so they stand up too. In the end, everyone in the cinema is standing. No one can see better than before, and what is more, standing is more uncomfortable than sitting. In fact, now the situation is even more unfair than before, as small people can’t see anything.

This example has a lot in common with the “big” resource management problems, for example over-fishing. Such problems are difficult to solve because they have two dimensions, as the cinema example shows:

- What rule do the visitors in the cinema need to guarantee everyone a good view?

(The issue.) - In what way can this rule be enforced if someone in the cinema breaks it?

(The institutional dimension.)

Besides overfishing, examples of “big” resource management problems are global warming, disposal of nuclear waste, and overconsumption of groundwater supplies. Many players with competing interests are involved (the issue dimension). On a global level, there is no super-state that can enforce a rule on a sovereign state (the institutional dimension). But the pressure of problems like global warming and climate change is mounting, and therefore political leaders and citizens around the world must make an effort to find a solution.

The fishing game addresses the problem of overfishing, focusing on the issue of sustainability, the first dimension of the problem. The task would become too complex for the students if it also included the institutional dimension; however, it is possible address the institutional dimension by extending and linking the fishing game to unit 5. See the introduction to unit 5 for further information on this option.

2. The fishing game

The fishing game is the key task in this unit, adopting a task-based learning approach. The students face a problem and must find a solution – under time pressure – as they often must in reality. The students reflect on their experiences in lessons 3 and 4.

In the fishing game, the students face the problem of how to manage a common resource. The fishing game is designed around a scenario that seems to be quite simple. The students form four groups and act as four crews of fishermen living in villages around a lake. The fish stock in the lake is the fishermen’s common resource, and their only source of income. The students will immediately become aware that their common interest is to avoid overfishing their fish stock.

However, there are no rules in place, nor are there any institutions such as a fishermen’s community council where the players could communicate and discuss the problem. Nor do the fishermen have any idea how many fish they can catch without damaging the reproduction of the fish stocks. The students have the task to identify all these problems, and to take action.

The teacher manages the game. Before the game starts, the players receive the deliberately ambiguous Instruction, “Catch as many fish as you can.” The players can read this Instruction in two ways:

- “As an individual team, maximise your income.” (Short-term profit maximisation.)

- “As a community, make sure that you catch as many fish as you can in the long run.” (Long-term sustainability.)

Experience has shown that the students usually adopt the goal of short-term profit maximisation. Some groups catch less, and soon discover that they are not only poorer, but that they cannot save the fish stocks by an unco-ordinated effort. A scenario rapidly unfolds in which the fish stocks are in danger of being exhausted, and a gap between rieh and poor villages develops. The players may have strong feelings, as the game first produces winners and losers, before the community as a whole slips into poverry.

The students face a daunting challenge:

- They must make a joint effort to solve the problems.

- They must begin to communicate.

- They must collect Information on the reproduction of the fish stocks and devise a scheme for sustainable fishing.

- They will discover that they need an institutional framework to make sure that everyone follows the rules that they have agreed on to save the fish stocks.

- Finally they must agree on a rule on how to distribute the catches fairly.

The fishing game, as simple as its design may seem, takes the students to the heart of some of the global issues of the 21st century, and it offers them experience of what politics is about – solving urgent problems that endanger a community, or even mankind.

3. Reflection

The students may sueeeed in solving some of the problems they are involved in, or they may fail. It is important that in the reflection phase, the students understand that such a failure is nothing to be ashamed of. For one, failure is the more common outcome in reality than success, and second, the fishing game is not a school task, but stands for a complex political problem. No one knows the appropriate solution to a political problem beforehand; we must try to find one.

In the fishing game, the students have discovered a complex set of questions some of which can be linked to the model of sustainability (student handout 4.2):

- What is the optimum level of fishing that is compatible with the reproduction of the fish stocks?

- How can we make sure that this balance of maximum output (goal of economic growth) and protection of the fish stocks (goal of environmental protection) works permanently, today and in future?

- What is a fair distribution of work effort and fishing output among the four villages in the community?

Sustainability model (student handout 4.2)

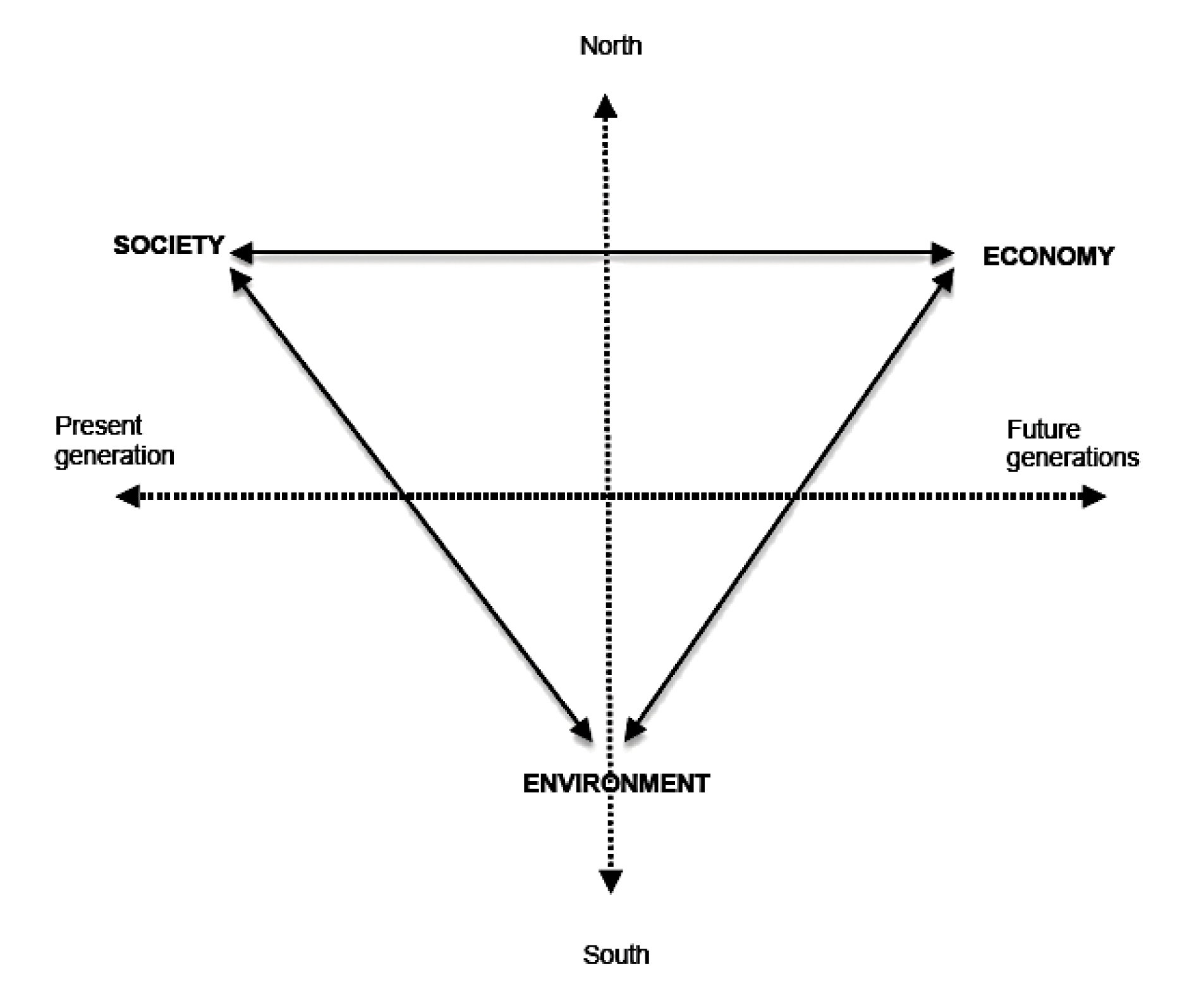

The model of sustainability includes all three questions. They stand for the three basic goals of economic growth, environmental protection, and distributive justice in society; they are linked to the two dimensions of time (the interests of the present and future generations), and space (the global dimension – north and south).

The model of sustainability describes both the dilemmas that emerge if a player attempts to achieve only one goal, for example profit at the expense of resource protection, and a balance of goals in a successful strategy of sustainability. Student handout 4.3 guides the students to reflect on the implications of “catching as many fish as possible” from these two perspectives – the goal of temporary profit gains for one player, and from the perspective of a sustainability balance.

Within the game setting, an optimum solution is possible and can be defined in figures; the teacher can supply this solution (student handout 4.4) to support the students if necessary.

This analysis will prompt the students to raise the question of why achieving sustainable development on a larger scale is so difficult, and what the individual citizen can do to support this goal.

Options for extending the unit

1. Linking units 4 and 5

As already mentioned above, the students can explore the question of what institutional framework serves the fishermen’s needs best. This can be a framework of rules, and a body of state authority to enforce it, or a mutual agreement between equals. The students can continue the fishing game and apply their Institution as a tool, thereby putting it to the test.

2. Research task

It is obvious that the fishing game stands for political issues ranging from those in the local community to those at the global level. As mentioned above, CO2 emissions, overfishing, nuclear waste disposal, and overconsumption of groundwater supplies are examples of such issues.

A study of one of these, or other issues, is possible both in an extension in class, or as a research project. In this case, the students are given a lesson to report on their findings, and perhaps discuss further steps to be taken.

The key concept of conflict

|

All of us have experienced conflict, and for most of us it is unpleasant. In pluralist societies the differences between people with different interests and values tend to increase, which increases the potential for conflict. Political communities face the challenge of finding ways of dealing with conflict. Democracy is a system that attempts to civilise conflict. It delivers a framework in which to act out conflict not though violence, but through the spoken word. The exchange of arguments and a clear articulation of different interests is even useful, as it gives a clear picture of the needs and interests that the different groups in society have and which should be considered when making decisions. In pluralist societies with a democratic constitution, conflicts are usually settled by compromise. This works best if the conflict is about the distribution of a scarce resource, e.g. income, time, water, etc. Conflicts that focus on ideology – different values, religious beliefs, etc. are more dif-ficult to settle by compromise; here some mode of peaceful co-existence must be found. Conflicts that centre on identity – colour, ethnic origin – cannot be settled, but need to be contained by a “strong state”. Potential for conflict is present wherever and whenever people interact with each other. In EDC/ HRE, the students may learn to understand conflict as something “normal” that they need not be afraid of. Indeed they must possess the skills to handle conflict through negotiation and respon-sibility – the willingness to consider the perspectives and interests of others, and to protect the rights of all to participate in peaceful conflict resolution. This manual can therefore be read as a series of training sets for skills in conflict resolution. Taking part in democracy means taking part in settling conflict. |

Competence development: links to other units in this volume

What this table shows

The title of this manual, Taking part in democracy, focuses on the competences of the active citizen in democracy. This matrix shows the potential for synergy effects between the units in this manual. The matrix shows what competences are developed in unit 4 (the shaded row in the table). The strongly framed column shows the competences of political decision making and action – strongly framed because of their close links to taking part in democracy. The rows below indicate links to other units in this manual: what competences are developed in these units that support the students in unit 4?

How this matrix can be used

Teachers can use this matrix as a tool for planning their EDC/HRE classes in different ways.

- This matrix helps teachers who have only a few lessons to devote to EDC/HRE: a teacher can select only this unit and omit the others, as he/she knows that some key competences are also developed, to a certain extent, in this unit – for example, taking responsibility, problem analysis, negotiation skills.

- The matrix helps teachers make use of the synergy effects that help the students to be trained in important competences repeatedly, in different contexts that are linked in many ways. In this case the teacher selects and combines several units.

| Units | Dimensions of competence development | Attitudes and values | ||

| Political analysis and judgment | Methods and skills | Taking part in democracy Political decision making and action |

||

| 4 Conflict | Conflict and dilemma analysis Interdependence Sustainability |

Identifying complex problems Negotiating |

Compromising Co-ordination of policies |

Willingness to compromise Responsibility |

| 2 Responsibility | Dilemma analysis | Considering consequences of choices | Mutual recognition | |

| 3 Diversity and pluralism | Conflict potential in pluralist societies | Negotiating | ||

| 5 Rules and law | “Rules are tools” to handle conflict | Problem analysis and solution | Designing and applying an institutional framework of rules to resolve conflict | |

| 6 Government and politics | Politics – a process of problem and conflict resolution | Description and analysis of political decision-making processes | Participating in public debates on decision making | |

| 7 Equality | Conflict between majority and minority groups | Designing means balancing group interests | Adopting the perspective of others | |

| 8 Liberty | The spoken word – the medium for civilised conflict resolution | Arguing | Strategies of argument | “Voltairian spirit”: appreciation of freedom of thought and expression for all |

UNIT 4: Conflict – The fishing conflict

How can we solve the sustainability dilemma?

| Lesson topic | Competence training/learning objectives |

Student tasks | Materials and resources | Method |

|

Lesson 1 The fishing game (1) |

Analysing a complex situation, making decisions under time pressure. The students become aware of dilemmas involved in maintaining sustainability. |

The students identify problems and develop solutions and strategies. | Materials for teachers 4.1-4.4. Pocket calculator or computer. Slips of paper (width A4), markers. |

Task-based learning. |

|

Lesson 2 The fishing game (2) |

Negotiating a compromise. Interdependence, conflict of interests. |

The students analyse a complex problem. The students (should) co-operate to develop a joint solution. |

The same as in lesson 1. | Task-based learning. |

|

Lesson 3 How do we catch “as many fish as possible”? |

Analytical thinking: linking experience to an abstract concept or model. Model of sustainability goals. |

The students reflect on their experience in the fishing game. | Student handout 4.2. Student handout 4.3 (optional). | Debriefing statements. Plenary discussion. Individual work. |

|

Lesson 4 How can we achieve sustainability? |

Analysis and judgment: Reflecting on experience through concept-based analysis. Incentives strongly influence our behaviour. The effect of incentives can be checked by rules (externally) or by responsibility (self-control). |

The students apply concepts to their personal experience. | Student handout 4.2. | Presentations. Plenary discussion. Teacher inputs. |

- Lesson 1: The fishing game (1)

This matrix sums up the information a teacher needs to plan and deliver the lesson. Competence training refers directly to EDC/HRE. The...

- Lesson 2: The fishing game (2)

This matrix sums up the information a teacher needs to plan and deliver the lesson. Competence training refers directly to EDC/HRE. The...

- Lesson 3: How do we catch "as many fish as possible"?

Debriefing and reflection This matrix sums up the information a teacher needs to plan and deliver the lesson. Competence training refers directly...

- Lesson 4: How can we achieve sustainability?

Ways to balance goals and overcome conflict This matrix sums up the information a teacher needs to plan and deliver the lesson....

- Materials for teachers 4.1: Fishing game: record sheet for players

Record sheet Boat No. Name Season No. Fishing quota (15% maximum) Catch (in tons, total amount) 1 2 3 4 5 6...

- Materials for teachers (game managers) 4.2: Reproduction chart: recovery of the fish population (in tons of fish)

At the end of the fishing season 47 tons of fish are left in the lake. In the close season, the population...

- Materials for teachers 4.3: Fishing game: record chart

Season No. Population of fish before season (tons) Boat No. 1 Boat No. 2 Boat No. 3 Boat No. 4 Total quota...

- Materials for teachers 4.4: Fishing game: diagram of fish Stocks and total catches

Tons 160 150 140 x 130 120 110 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Season No. 1...

- Materials for teachers 4.5: Homework Instructions (mini-handout for students)

The students receive the following Instructions for their homework. This page can be copied and cut into mini-handouts. A written Instruction is...

- Unit 4.5: Background information for teachers: Reading list on the fishing game

Reading list Garrett Hardin (1968), “The tragedy of the commons”, in Science, Volume 162 (1968), p. 1244, www.garretthardinsociety.org. Elinor Ostrom (1990), Governing...