Materials for teachers 3B: Lecture: what is the common good?

Living Democracy » Textbooks » Materials for teachers 3B: Lecture: what is the common good?This draft describes the basic guidelines of analysis. The teacher should adapt the lecture to the students’ learning needs and the context of the unit.

In democracies, it is understood that no one knows for sure what the common good is, and we therefore have to decide together what we consider to be best for our community. In dictatorships, the regime decides what the common good is – this is one of the big differences between democracy and dictatorship.12

Anyone can, and does, take part in this ongoing discussion: political parties, interest groups, the media, politicians, and individual citizens. Essentially, this is what taking part in democracy is all about – debating and finally deciding what is best for the country (or the world), and how to achieve this goal.

This unit is designed as a greatly simplified model of this decision-making process. You began by suggesting your individual ideas on the common good – when you think about your priorities if you were the leader of this country, you are thinking about the common good. Now you are in the middle of forming parties.

In the next lesson, you will negotiate with each other to find out if you can form a majority that defines the common good – for the time being.

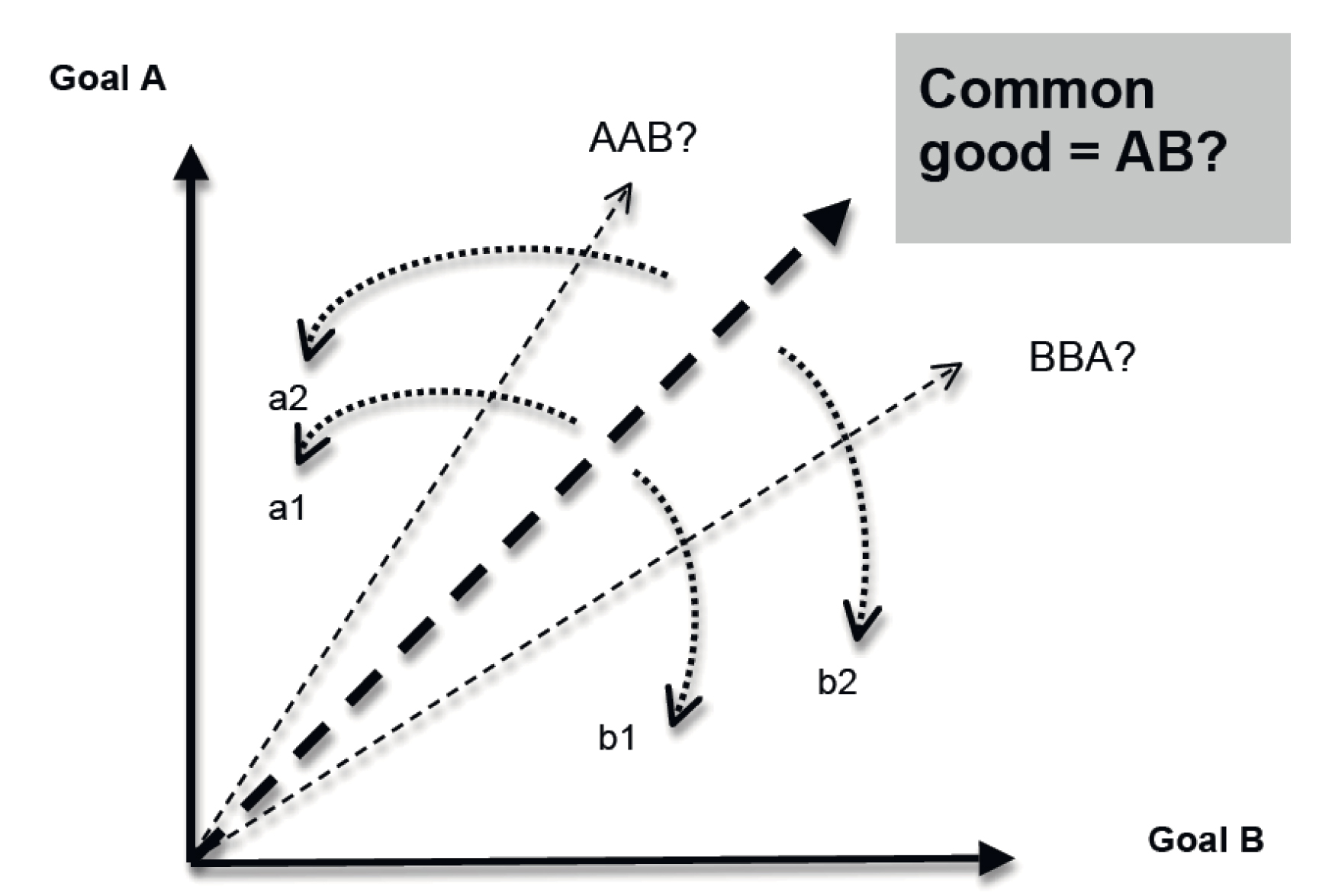

This diagram shows what happens in such a decision-making process. Suppose that there are two basic goals under discussion, goal A and goal B (these can be linked to concrete goals that the parties have presented). The three dotted arrows indicate the final choices that the parties advocate – some would like to give priority to goal A (variant AAB), others to goal B (variant BBA). These are different ideas of compromise. Each party stands for a certain agenda that supports certain group interests in society, and it offers to take the interests of the other side into consideration.

The parties therefore try to influence decision making in their direction – a1 and a2 in favour of goal AAB, with the parties b1 and b2 pulling in the opposite direction (BBA).

What option is the best in terms of the common good: AAB or BBA? Or is it perhaps a balance more in the middle: AB? A decision must be made. The parties negotiate, and try to find a compromise that they can agree on, and therefore support together. In democracies, compromise is the price to pay for power. The power to decide rests with the majority. The minority, or individuals, can influence the decision by good reasoning.

Decisions made in this way are permanently subjected to critical review. The decision may not serve the common good after all. Conditions may change. Majorities may change. The majority may be convinced by good reasoning to change their minds. A democratic community is a learning community.

Extension (this part can be given separately)

How is all this linked to the key concepts of this unit – diversity and pluralism?

By exercising their freedom of thought and expression, individual citizens create a widely diverse spectrum of individual opinions on what is best for the country. Citizens who are interested in seeing their goals turned into practice form or join organisations such as parties, interest groups, etc. This is organised pluralism (see a1, a2, b1, b2 in the diagram).

Pluralism generates competition for power and political influence. A decision requires some goals and interests to be prioritised, while others are rejected. A compromise is sometimes necessary to achieve a sufficient majority.

Citizens who do not take part in this game by articulating their interests and views loudly and clearly will find themselves left out. It is in everybody’s interest to take part in democracy.

12. See student handout 3.6 for a more detailed treatment of this point.