1.1.1 Politics – power play and problem solving

Newspaper readers or TV news watchers will find that many media reports on politics fall into one of the following two categories:

- Politicians attack their opponents. In doing so, they may question their rivals’ integrity or ability to hold office, or deal with particular problems. This perception of politics – as a “dirty business” – makes some people turn away in disgust.

- Politicians discuss solutions to solve difficult problems that affect their country or countries.

These two categories of political events correspond to Max Weber’s classic definition of politics:

- Politics is a quest and struggle for power. Without power, no political player can achieve anything. In democratic systems, political players compete with each other for public approval and support to win the majority. Therefore, part of the game is to attack the opponents, for example in an election campaign, to attract voters and new party members.

- Politics is a slow “boring (of) holes through thick planks, both with passion and good judgement”.4The metaphor stands for the attempt to solve political problems. Such problems need to be dealt with, as they are both urgent and affect society as a whole, and are therefore complex and difficult. Politics is something eminently practical and relevant, and discussion must result in decisions.

Politics in democratic settings therefore requires political actors to perform in different roles that are difficult to bring together. The struggle for power requires a charismatic figure with powers of rhetoric and the ability to explain complex matters in simple words. The challenge of solving the big problems of the day, and our futures, demands a person with scientific expertise, responsibility and integrity.

1.1.2 Politics in democracy – a demanding task

Of course, we first think of political leaders who must meet these role standards that tend to exclude each other. There are prominent examples of leaders who stand for the extremes – the populist and the professor. One tends to turn politics into a show stage, the other into a lecture hall. The first may win the election, but will do little to support society. The second may have some good ideas, but only a few will understand them.

However, not only political leaders and decision makers face this dilemma, but also every citizen who wishes to take part in politics. In a public setting, speaking time is usually limited, and only those speakers will make an impact whose point is clear and easy to understand. Teachers will discover that there are surprising parallels between communication in public and communication in school – the scarcity of time resources, the need to be both clear and simple, but also able to handle complexity.

Exercising human rights – such as freedom of thought and speech, taking part in elections – is therefore a demanding task for all citizens, not only political leaders. In EDC/HRE, young people receive the training in different dimensions of competences, and the encouragement that they need to take part in public debates and decision making. As members of the school community, students learn how to take part in a society governed by principles of democracy and human rights.

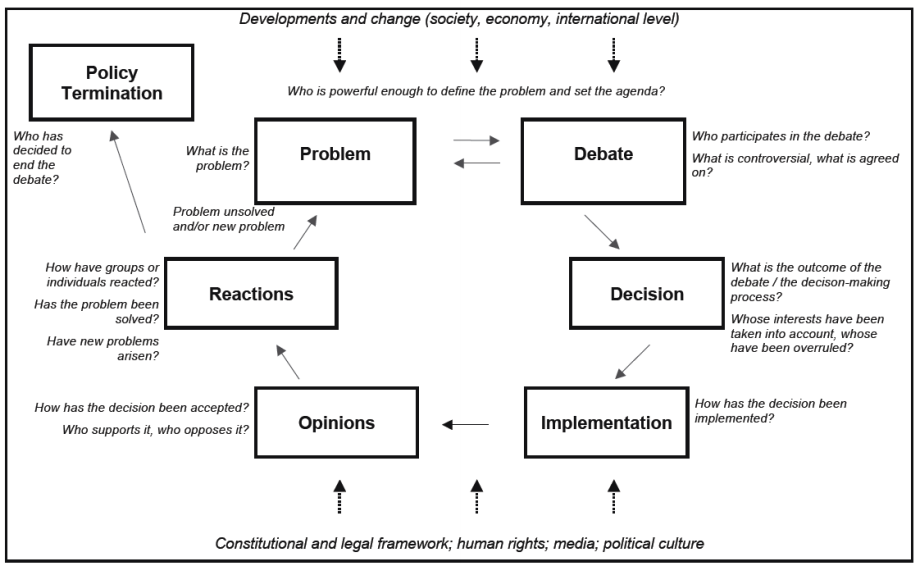

1.1.3 The policy cycle model: politics as a process of solving problems in a community

Politics is conceived as a process of defining political problems in a controversial agenda-setting process, and both in defining a political problem and excluding other interests from the agenda, a considerable element of power is involved. The model gives an ideal-type description of the subsequent stages of political decision making: debating, deciding on and implementing solutions. Public opinion and reactions by those persons and groups whose interests are affected show whether the solutions will serve their purpose and be accepted. Minorities or groups too weak to promote their interests who have been overruled may be expected to express their protest and criticism. If the attempt to solve a problem has succeeded (or has been defined as success-ful), the policy cycle comes to an end (policy termination); if it fails, the cycle begins anew. In some cases, a solution to one problem creates new problems that now must be seen to in a new policy cycle.

The policy cycle model emphasises important aspects of political decision making in democratic systems, and also in democratic governance of schools:

- There is a heuristic concept of political problems and the common good; no one is in a position to define beforehand what the common good is. The parties, groups and individuals taking part in the process have to find out and usually agree to compromise.

- Competitive agenda setting takes place; in pluralist societies, political arguments are often linked to interests.

- Participation is imperfect in social reality, with certain individuals and groups systematically having less access to power and decision-making processes, thus being a model that requires attention to increasing the access of less powerful.

- Political decision making is a collective learning process with an absence of omniscient players (such as leaders or parties with salvation ideologies). This implies a constructivist concept of the common good: the common good is what the majority believes it to be at a given time.

- There is a strong influence of public opinion and media coverage – the opportunity for citizens and interest groups to intervene and participate.

The policy cycle is a model – a design that works like a map in geography. It shows a lot, and deliv-ers a logic of understanding. Therefore models are frequently used in both education and science, because without models we would understand very little in our complex world.

We never mistake a map for the landscape it stands for – a map shows a lot, but only because it omits a lot. A map that showed everything would be too complicated for anyone to understand. The same holds true for models such as the policy cycle. Nor should this model be mistaken for reality. It focuses on the process of political decision making – “the slow boring of holes through thick plants” – but pays less attention to the second dimension of politics in Max Weber’s definition, the quest and struggle for power and influence.

In democratic systems, the two dimensions of politics are linked: political decision makers wrestle with difficult problems, and they wrestle with each other as political opponents. In the policy cycle model, the stage of agenda setting shows how these two dimensions go together. To establish an understanding of a political problem on the agenda is a matter of power and influence.

Here is an example. One group claims, “Taxation is too high, as it deters investors,” while the second argues, “Taxation is too low, as education and social security are underfunded.” There are interests and basic political outlooks behind each definition of the taxation problem, and the solutions implied point in opposite directions: reduce taxation for the higher income groups – or raise it. The first problem definition is neo-liberal, the second is social democrat.

Citizens should be aware of both. The policy cycle model is a tool that helps citizens to identify and judge political decision makers’ efforts to solve the society’s problems.

4. Weber M. (1997), Politik als Beruf (Politics as a vocation), Reclam, Stuttgart, p. 82 (translation by Peter Krapf).