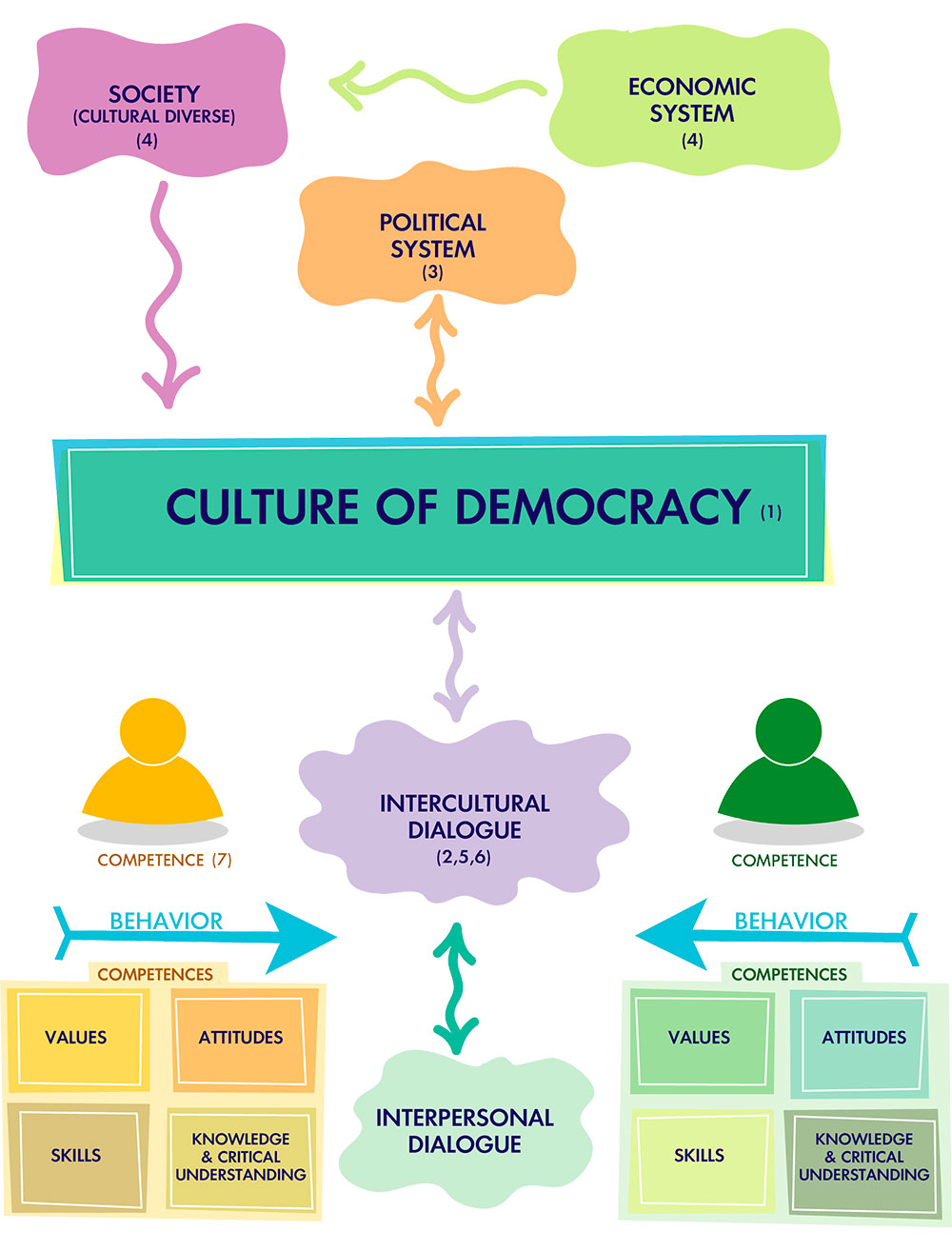

Competences for democratic culture: a diagram

Living Democracy » Principals » LEARNING » Preparation » Competences for democratic culture: a diagramSource: See Competences for Democratic Culture Figures no 1 – 7 refer to the notes.

Diagram of Competences for democratic culture: notes

Page numbers refer to Competences for Democratic Culture

This diagram is an attempt to visualize the conceptual model of competences that citizens need to create, and participate in, a culture of democracy (see p. 9). A model is designed to resemble reality in a simplified way, focusing on some key aspects and omitting many others. A road map, for example, is a model of the road network in a certain area, which is useful because it shows so little else. Likewise, the model of competences for democratic culture works like a map. It shows how our behavior as individuals is linked to democratic culture as a whole, and how schools can play their part to educate their students for democratic citizenship.

The diagram and the following notes are intended to assist the readers of the manual Competences for democratic culture, but it does not replace it. They are intended for in-service training for teachers and principals, or information for parents and external stakeholders.

1. The institutional framework of democracy (the political system) cannot function or survive unless it is supported by a culture of democracy that all citizens share. In such a culture of democracy, citizens are committed to observe the rule of law and human rights and to resolve issues of general concern in public. They are convinced that conflicts must be resolved peacefully, and they acknowledge and respect diversity in society. Citizens are willing to express their own opinions, as well as to listen to the opinions of others. They are committed to a decision-making process based on majority vote as well as to the protection of minorities and their rights. They are willing to engage in dialogue across cultural divides (see p. 15). The institutional structures of democracy and the culture of democracy are “inherently interdependent” (p. 15), which means neither area is self-sustaining if not supported by the other. The strength of the culture of democracy depends not only on competent citizens, but also to what extent the key elements mentioned above are shared rather than contested or disputed (see note 6).

2. When citizens participate in discussions and decision-making, they meet others whose cultural background is different. Intercultural dialogue between citizens is therefore the hallmark of culturally diverse democratic societies. Citizens who are willing to engage in dialogue across cultural divides treat each other as democratic equals. Intercultural dialogue needs to be embedded in a culture of democracy, and vice versa a democratic culture cannot thrive without an intercultural dialogue. Democratic culture and intercultural dialogue are “inherently interdependent” (p. 15), linking the macro level of society to the micro level of interaction between individuals. This idea is summed up in the logo of this website, Living Democracy.

3. Competent citizens are a necessary precondition for democratic culture and intercultural dialogue, but competences alone are not sufficient. The effect of political institutions on the macro level is crucial: “… depending on their configuration, institutional arrangements can enable, channel, con¬strain or inhibit the ways in which citizens exercise their democratic and intercultural competences.” (p. 17) For example, citizens who are able and willing to participate in decision-making need access to uncensored media information, and they need channels through which they can communicate with each other and with policy makers.

4. There is a second bundle of factors on the macro level that may produce “systemic patterns of disadvantage and discrimination” (p. 18) so that citizens who have equal levels of democratic and intercultural competences face unequal opportunities to exercise them and to participate in decision-making. Social inequality may be due to show in unequal distribution of income, disposable time, access to information or communication networks, and power resources. The unequal allocation of resources within societies are linked to the economic system (e.g. unequal pay, unemployment, power of international enterprises) and/or the political system. Divisions between privileged and disadvantaged groups may give rise to issues of gender inequality, poverty, migration, education, or control of power. “Systematic marginalisation and exclusion from democratic processes and intercultural exchanges” (p. 18) may disempower many citizens to participate on equal terms, regardless of their levels of competence, resulting in “civic disengagement and alienation” (ibid.).

5. If not adequately addressed, social inequality may be perceived as unfair and may threaten the democratic culture and the legitimacy of the institutional framework of democracy. In democratic communities, it is therefore crucial to deal with issues of social inequality and exclusion to ensure “genuine equality of condition” (ibid.) for all citizens. That said, it is important to remember that distributive justice, or human and civil rights are historic achievements taking place over a long period of time, as the struggle for universal suffrage and women’s rights across Europe shows. Human rights and democratic participation have developed in a long, still on-going process. The commitment of competent citizens is therefore decisive to ensure that all members of society, regardless of their social status, enjoy recognition and equal opportunity of participation.

6. The concept of culture: “Any given culture may be conceived as having three main aspects: the material resources that are used by members of the group (e.g. tools, foods, clothing), the socially shared resources of the group (e.g. the language, religion, rules of social conduct) and the subjective resources that are used by individual group members (e.g. the values, attitudes, beliefs and practices which group members commonly use as a frame of reference for making sense of and relating to the world). The culture of the group is a composite formed from all three aspects – it consists of a network of material, social and subjective resources.” (p. 19; italics added by the authors) However, cultural groups are internally heterogeneous. Cultures and norms are disputed, and change over time. Individual members in a cultural group make their choices in adopting certain subjects of cultural resources and rejecting others.

Any social group can have its distinctive culture. These groups include nations, ethnic or religious groups, cities, neighborhoods, work organizations, occupational, LGBT community, disability or generational groups, and families. Societies are therefore culturally diverse, individuals who simultaneously belong to different social groups and participate in different, individually unique, constellations of cultures. Within a cultural group, individuals differ in cultural positioning, which is why cultural resources are disputed within cultural groups.

In any situation in which people interact with each other, they may perceive differences in culture in the other person or group, so “every interpersonal situation is potentially an intercultural situation” (p. 20). Our frame of reference may therefore shift from the individual and interpersonal to the intercultural, which means we perceive others as members of a social group rather than as individuals. Such intercultural situations may arise when we meet people from different countries or ethnic groups, of different faith, gender, sexual orientation or social class, or we notice differences in education. Intercultural dialogue has the potential to build bridges between cultural groups, provided it is enacted as “‘an open exchange of views, on the basis of mutual understanding and respect, between individuals or groups who perceive themselves as having different cultural affiliations from each other.’” (p. 20 f.)

Intercultural dialogue is of utmost importance to strengthen the social cohesion in culturally diverse, democratic societies. However, if cultural groups perceive each other as enemies, for example because of armed conflict in the past, or one cultural group is perceived as enjoying privileges at the expense of the other, intercultural dialogue may prove very difficult, requiring a high level of intercultural competence, empathy, personal strength and courage (see p. 21).

7. The concept of competence and competences: (p. 23 ff.) In the model of competences for democratic culture, the concept of competences (in the plural) refers to an individual’s “psychological resources” – values, attitudes, skills, knowledge and/or critical understanding. We may imagine these resources to resemble a big toolbox with a large variety of mental and psychological tools. Competence (in the singular) refers to the willingness and ability of a person to make use of these competences, or tools, as deemed adequate in a given situation, or to deal with a problem. The concept of competence stands for a “dynamic process” (p. 24) in which a person selects, activates, organizes and co-ordinates the psychological resources (competences) in a given situation, and monitors and adapts the deployment of competences depending on contingent conditions. Competences are used in clusters rather than separately. Competence and competences are invisible, and only accessible through theories and models. They are visible in a person’s behavior, i.e. what someone does, thinks, says, or how a person interacts with others. Teachers may therefore assess their students’ level of competence development by observing their behavior in democratic or intercultural situations. The manual on the competence model for democratic culture describes three examples to show how clusters of competences are mobilized in certain situations: intercultural dialogue, standing up against hate speech, and participation in political debate (see p. 24 f.).

8. In order to empower future citizens to participate in a culture of democracy at the macro level, children and youth need to learn and practice competences for democratic culture and intercultural dialogue at the micro level of society, in the school community (see p. 16). This requires that the school adopt Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights (EDC/HRE) as a whole-school approach, which means teaching and learning about, through, and for democracy and human rights – democracy and human rights being a subject matter in class (“about”), a pedagogical guideline for the whole school (“through”), and preparation for participation through practical experience in school (“for”). For a fuller account on the three dimensions of EDC/HRE, see http://living-democracy.com/textbooks/volume-1/part-1/unit-3/chapter-1/. Teachers and principals need to acquire competences for democratic culture and practice them in school to deliver role models for their students. Diversity in society is mirrored in the school community and in class, so that interpersonal dialogue between teachers and students, and among students, always includes the dimension of intercultural dialogue. Learning for democratic culture will not suffice to change the whole of society at the macro level for the better, but without competent citizens, it will be impossible.