Democratic school leadership in practice: decision-making on school rules

Living Democracy » Principals » LEADERSHIP » Discipline through responsibility » Democratic school leadership in practice: decision-making on school rulesWho decides what?

Before a discussion on school rules takes place and decisions are made, it is essential that all stakeholders know their rights of participation. Either by law or through an agreement by your school community, you need to have school rules in place for participation – preferably in form of a permanent framework. For a more details, see Preparation Handout 3.1.

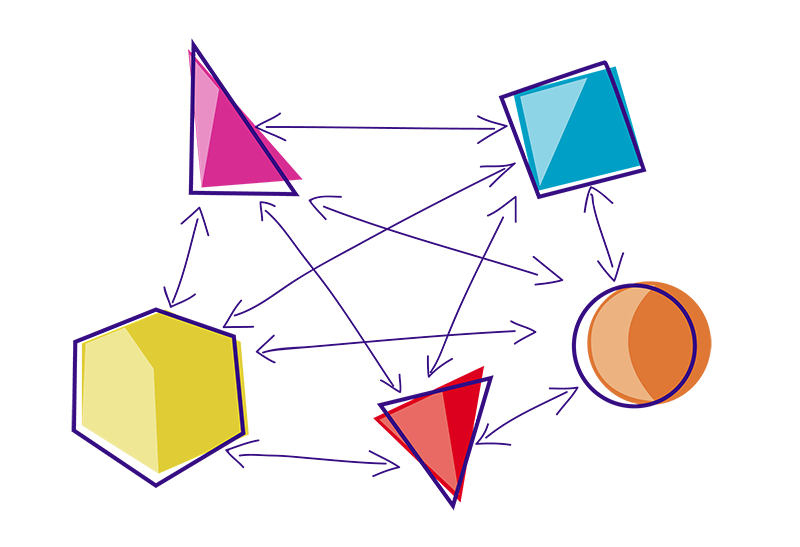

A model procedure in democratic school leadership: decision-making on school rules (adapted from the model in Action Handout 3.1).

1. Situation analysis: Why do we need new school rules?

- What kinds of problems are we dealing with (e.g. student behavior, implementation of school rules, effect of sanctions)?

- Why is this problem so urgent that we must we deal with it now?

- Which rules worked well? What can be kept?

- Which rules need to be changed or newly introduced?

- …

2. Discussion: What solutions are possible?

- How do we expect or wish that the members of our school community behave?

- What makes a good school rule?

- What choices do we have to improve or change our school rules? (Written, formalized school rules – or unwritten rules, informal agreements, appeals to shared interests and values)

- To what kinds of values do we adhere to in our rules?

- What kinds of sanctions should be in place?

- Do our new school rules comply with school legislation? (E.g. did we take the responsibilities of the teachers and the school principal ιnto account?)

- …

3. Joint decision and implementation

- Which option do we choose? Discussion among students, staff and parents.

- Majority vote by students and teachers.

- Final approval by the school council (see Preparation Handout 3.1).

- Master document signed by the school principal, head spokesperson for students and parents.

- The newly-adopted version of the school rules is shown on the school’s website.

- Copies or posters of the school rules are displayed in every classroom.

- …

4. Evaluation of the results

- The first review of the results takes place after a mutually agreed period of time.

- Has the problem been solved?

- Are there any unexpected effects? – Can we accept them?

- Can we leave the rules in place as they are? Or should we begin a new cycle of decision-making to adapt or improve the rules?

- …

5. Evaluation of the decision-making process; reflection and lessons learned

- Do the students, teachers and parents feel that they were adequately involved?

- Did they have an opportunity to express their views and ideas?

- Did their input have an impact on the result?

- Do we consider the way this decision was made an example of democratic school leadership?

- Conclusions for future decision-making: what worked well, and what should be improved? Can, or should we find ways to get students more heavily involved?

- What did the students learn? (E.g. Democratic communities are learning communities. –

- The enforcement of rules should be the exception rather than the norm.

- All members of the community should share an attitude of mutual respect, responsibility and civic-mindedness so that we need not permanenty control and observe each other).

- …

The balance between participation and efficiency

It is obvious that a whole-school decision-making process, involving all stakeholders, particularly the students, is a major project that requires time (see Action Handout 2.1). The model outlined here focuses on the participation by all stakeholders and the learning opportunities for students.

It is unrealistic to believe that all decisions in school life can be made in such a manner, as neither the school leaders and teachers, nor the parents could meet their professional obligations. Moreover, the majority of students would probably lose interest. Therefore, a balance must be found between the participation of stakeholders in the school and its efficiency as an educational institution.

This balance can be achieved by the following means:

- Not all stakeholders in school will be actively involved in many, if not most decision-making processes. A major part of the school administration and teaching activities will remain the responsibility of the school principal and teachers. The quality of democratic school leadership is evident in its sharing of information and listening to feedback.

- An institutionalized framework of representative democracy (see Preparation Handout 3.1) reduces the time strain for the vast majority of school community, while decisions by the school principal and staff are open to critical observation and discussion.

- Large-scale participation projects that involve all stakeholders are appropriate whenever an issue directly affects student interests and needs, and the students assume the role of experts.

- Therefore, one or more major participation projects should be conducted every school year. This could involve a “top down” version, such as a discussion between the school principal, the staff, and the head spokespersons of students and parents. It could also be a “bottom up” version, such as an agenda-setting initiative of the students (see Awareness Handout 3.2). In this case, the school principals and teachers should welcome and support the students’ initiative for its contribution to a democratic school culture, regardless of whether they agree with the students’ ideas or not.